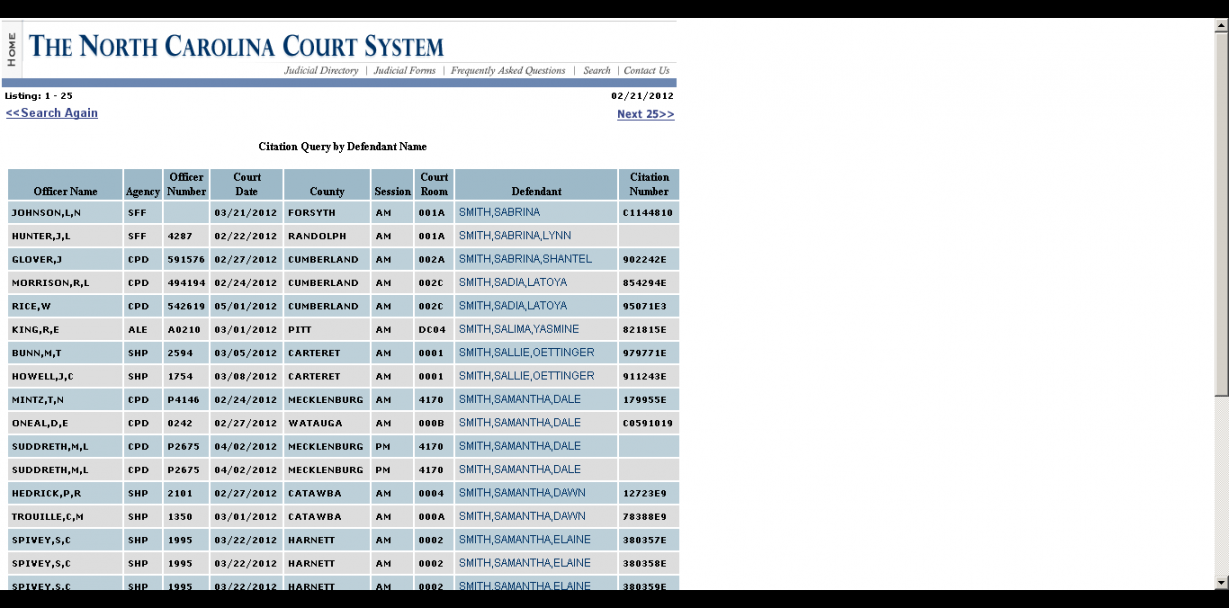

Nc Courts Query By Name

On race, the NC Supreme Court is building a bridge – to 1953 | Opinion

Many North Carolinians find it difficult to understand why Anita Earls, the only Black woman on our state Supreme Court, is being investigated for raising questions about the “racial, gender or political bias” of the court system while Paul Newby and Phillip Berger, Jr., two of the most partisan flamethrowers ever to sit on the high tribunal, remain secure, likely anxious to review the charges against Earls upon the Judicial Standards Commission’s recommendation.

It doesn’t seem right. It isn’t.

But the continuing specter of race doesn’t appear only in external attacks on particular members of the N.C. Supreme Court. It touches directly the judicial decisions of our state’s highest tribunal.

Two of the path-breaking rulings announced last summer by the N.C. Supreme Court, creating a major “course correction” in judicial decision-making, Holmes v. Moore and Community Success Initiative v. Moore, overturned prior trial court findings of race discrimination. Holmes reinstated the state’s voter ID law and Community Success Initiative resurrected a felony disenfranchisement provision, kicking 55,000 Tar Heels off the voter rolls.

Both cases involved restrictions on the franchise which were knowingly adopted despite having disproportionate impact on Black people in North Carolina. Both cases adopted new standards making it notably more difficult to prove race discrimination in N.C. cases. Both created markedly powerful presumptions in favor of the enactments of the N.C. General Assembly.

Justice Berger wrote the opinion in Holmes. He began, of course, with an ode to the General Assembly: “the great and chief department of government (representing) …the sacrosanct fulfillment of the people’s will.” Berger also bristled at the trial court’s attention to North Carolina’s brutal and vote-suppressing racial history:

“The world moves and we must move with it. The Lieutenant Governor, two members of this Court, and the minority leaders of the N.C Senate and House of Representatives are the most recent examples of the significant social progress made in North Carolina. The imputation of wrongs committed in the distant past to current realities is unjust and disingenuous.”

Justice Michael Morgan, one of the (then) referred to Black justices, refused, in dissent, to let Berger’s condescending “callousness” pass without comment:

“North Carolina’s long history of race discrimination is not one that can be legitimately denied, although the majority (argues) that the current presence of one Black man and one Black woman who were both elected to this Court, coupled with others who are members of the Black race who have also been elected to office in modern times, proves this state has progressed so much that (its) contemptible racial history regarding electoral politics bears no logical relation to its present-day political climate. This naivete, if such, would be appalling; this callousness, if such, would be galling.”

The exchange was particularly instructive in a judicial ruling in which the five white Republican members of the N.C. Supreme Court majority lectured the court’s two Black dissenting members about how race discrimination can be demonstrated and proven, what its impacts may be in the broader society, and how such wounds have been experienced, over time, in the Tar Heel state.

Cases like Holmes and Community Success fit snugly into a broader North Carolina agenda in which white Republican politicians decide for everyone else what can be taught about race in the schools, what brutal police videos can be seen by the public, what “diversity” policies can be pursued by institutions, and which Black Lives Matter protests are appropriately passive and civil.

Building a bridge to 1953.

Contributing columnist Gene Nichol is a professor of law at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.