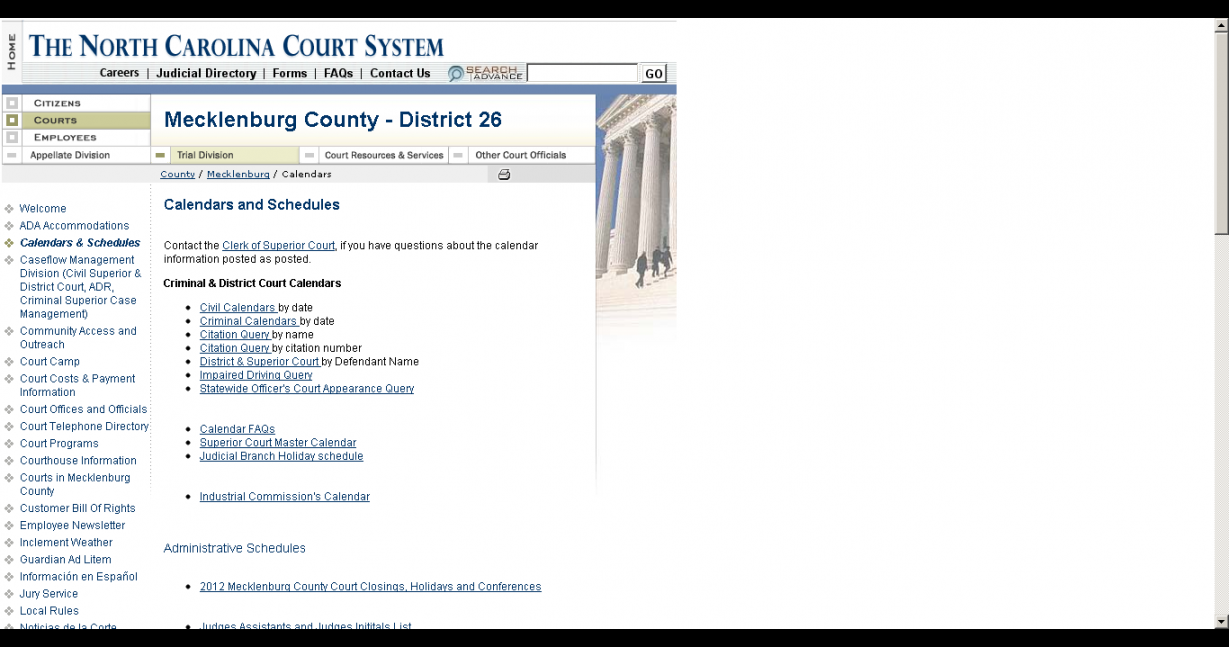

Aiken County School Calendar

In-school violence is rising. Here’s what happened when a fight erupted at Aiken High.

Student: Not good at Aiken High School. This is crazy.

Parent: Any clue what’s going on?

Student: Big fight. Someone pulled out something. I was right next to it and everyone started running.

Over 500 students filled Aiken High’s cafeteria. They bent over their trays, gossiping about their classes and friends. Some typed on their phones while eating pizza. Others sipped from milk cartons. The scene felt like an idyllic slice of American teen life that could have been lifted from a Freeform series or a high school romantic comedy. The only peculiarity was the adults standing on the cafeteria’s sidelines, watching intently.

One student stood up. Others joined. Some opened their camera phones and pressed record. A fight was about to start.

Students knew the warning signs. They could sense the energy changing. The older students had made it through a chaotic week of fighting at the end of last school year, instigated by a social media challenge. Many witnessed minor skirmishes that broke out the previous week, the first week of school. Some of their parents said they were numb to the violence.

But the fight Aug. 3 was different.

This time, half of the school’s nearly 1,200 students, stampeded out of the cafeteria because they were afraid someone had a weapon. They ran through halls painted in the school’s colors, dark green and gold. They threw open the glass front doors and sprinted away from the building as heat from the balmy, 90-degree day enveloped them. It was the eighth day of school.

Aiken Department of Public Safety (Facebook)12:52 p.m.There is currently a large law enforcement presence at Aiken High after the City of Aiken Aiken Department of Public Safety responded for a fight in progress. The situation is under control at this time and there are no current threats to any students.

S.L. (Facebook)1:22 p.m.If anybody have kids at the Aiken high school, please call and check on them. Apparently, a big fight has broken out. The school is on lock down some of those boys was caught with guns and knives. Please check on your kids and the school will notLet anyone in or anyone can go out.

T.L. (Facebook)1:39 p.m.Pray for our students! Stabbing during a fight at Aiken High School!

E.E. (Facebook)2:43 p.m.Damn, Fight, guns and stabbing at Aiken High School…already.

Jana Jackson read messages on Facebook about the fight at Aiken High and thought, “Not again. Another one?”

Her son, a senior, hadn’t gone to school that day, but she was concerned about the other students. Facebook posts about the fight were increasing at an alarming speed. Parents she knew were messaging her about the incident. She saw a picture of police cars and an ambulance outside the school.

She wondered who was injured and if it was someone she knew. She debated unenrolling her son, quickly weighing safety concerns against the social-emotional repercussions of transferring.

Jackson was angry. Not just about the fight but also about the lack of response from school officials. It was early afternoon, and the district still hadn’t told parents what happened.

She stayed glued to her phone, waiting for updates.

Police and emergency medical personnel responded to Aiken High School on Aug. 3, 2023, after the school was placed on soft lockdown following a fight. File/Kyle Dawson/Staff

Staff photo by Kyle Dawson

Aiken High wasn’t the only school in South Carolina where violent incidents occurred during the first weeks of the academic year.

On Aug. 10, an assistant principal in Marlboro County was injured trying to break up a fight between two high school students. Surveillance footage showed him running toward the students, crashing into them and falling to the ground. The students continued fighting, and he went to pull one of the teens off the other. The assistant principal wrapped his arms around one student’s neck, outraging people in the local community.

A screenshot of a video sent by the Marlboro County School District shows administrators trying to break up a fight at Marlboro County High School on Aug. 10, 2023. Marlboro County School District/Provided

“Marlboro County School District works diligently to maintain students’ safety; however, there are unintended consequences when students make poor decisions,” the district said in a statement.

Days later, a high school student in Union punched a classmate twice in the face in the cafeteria, according to news reports. The student was charged with assault. And on Aug. 24, officers from the Charleston Police Department were called to an elementary school after a student stabbed a staff member in the arm with a pencil. The employee had to go to the hospital for treatment.

Experts say that fighting picks up the first couple weeks of school when students return from summer vacation and are adjusting to classroom social norms. But the incident at Aiken High and other schools is part of a statewide problem of in-school violence returning to pre-pandemic levels.

South Carolina public schools reported 2,014 physical attacks without weapons in the 2021-22 academic year, according to state Department of Education data. This was perpetrated by only a small fraction of the over 777,000 students enrolled in the state’s K-12 public schools that year. But it was roughly in line with the number of fights reported pre-pandemic — 1,807 in 2019 and 2,185 in 2018 — and shows in-school violence is growing.

Police and emergency medical workers responded to Aiken High School on Aug. 3, 2023, after the school was placed on soft lockdown following a fight. File/Kyle Dawson/Staff

Staff photo by Kyle Dawson

Clara Walker was sitting at her desk when the phone rang. It was a co-worker who, like Walker, had a child at Aiken High. She told Walker that she needed to call and check in with her daughter. There was an altercation at the school, and police were called.

Walker’s daughter immediately picked up. She said she was leaving the cafeteria when the fight started. A crowd of students rushed out while others ran toward the incident. Walker’s daughter sounded like she was having an anxiety attack. She said Aiken High was on soft lockdown and that school leaders were starting to bring students back to class. Walker hung up and told her supervisor she needed to go. She needed to take care of her girl.

A group of parents gathered outside the brick building that displayed the school’s name in black letters. The parking lot was jammed with cars. A bunch of parents were trying to speak to two police officers stationed outside the school’s entrance. Some were holding young children while others were on their phones. The school district still hadn’t released any information about the fight. Cars kept pulling into the parking lot filled with people desperate for answers.

Parents stand outside Aiken High School on Aug. 3, 2023, after the school was placed on soft lockdown following a fight. File/Bianca Moorman/Staff

Staff photo by Bianca Moorman

Heather Thurmond navigated around the vehicles in the parking lot and waited for her son to get into the car.

School officials finally released a statement at 2:09 p.m. — more than an hour and a half after the fight began.

The school said law enforcement secured the scene, and students were safe in their classrooms.

“We recognize how alarming this situation is for all and have appreciated your patience and cooperation as we have worked hand-in-hand with law enforcement to ensure the safety of our students and families,” the school said.

It said law enforcement didn’t find a firearm at the scene.

More Information

The Post and Courier Education Lab is a multi-year project, employing four reporters, focused on the need for public education reform in South Carolina. The Coastal Community Foundation and Spartanburg Foundation serve as fiscal sponsors for the Education Lab, which is supported by grants from the Jolley Foundation, Intertech, anonymous donors, and generous donations on behalf of donors to The Post and Courier Public Service and Investigative Fund who designate to the Education Lab.

The district told The Post and Courier in an email that it needed to concentrate on securing the area and protecting students’ safety at the outset.

“We regret not having been able to send an initial notification with greater speed,” the district said.

Thurmond was disappointed with how long the school took to communicate with parents. When her son got into the car, he showed her a photo another student had taken of a knife found on the scene that was circulating on Snapchat.

She asked her son if he was scared. He said, “I’m good.” This response both reassured and worried her. She felt relieved that he wasn’t frightened but felt that after the fighting at the end of last school year, he was desensitized to the violence.

She spent the evening checking her phone for updates from the school about what happened.

Aiken police sent out the most detailed information about the fight. It began in the hallway outside the cafeteria between a couple of students, according to a public safety spokeswoman. It quickly grew as more people joined, with 10 ultimately participating. Six teenagers were brought in by police in the immediate aftermath. All were charged with misdemeanor affray, meaning they fought in a public place, terrifying others. Several students sustained minor injuries. One was brought to the hospital with a possible broken arm.

Aiken schools were faced with several ethical dilemmas: Should they expel the students? Increase security? Invest in long-term preventive measures like mental health support?

The district’s decisions over the following weeks reflect similar debates schools are having across South Carolina.

Hell week

Aiken County is on the western edge of the state along the Savannah River, which marks its border with Georgia. Of the county’s roughly 175,000 residents, 70 percent are White, according to census figures. In the city of Aiken, the county seat with 32,000 residents, that figure falls to just below 60 percent.

This is horse country rich in history, with large farms, pristine training grounds and miles of riding trails. Crowds gather on the sidelines of polo matches and along the rails to watch steeplechase races in the spring and fall, cheering as the horses tear apart the lush green fields. Horse jumping competitions, harness and Thoroughbred races, fox hunts and other equestrian events fill out the calendar.

Sign up for our Education Lab newsletter.

Andrew Siders performs the national anthem to help start the Sunday afternoon festivities on Whitney Field, including the title game of the U.S. Polo Association Constitution Cup, in June 2020. File/Bill Bengtson/Staff

Staff photo by Bill Bengtson

Walker was born and raised in Aiken County. She attended the city’s public schools and sent her daughter to an Aiken elementary school, middle school, and the high school on the south side of town. Right before her daughter’s junior year, Walker’s family moved to the north side of town, which is zoned for Aiken High. Her daughter transferred there for the 2022-23 school year.

Walker heard about the occasional fight at Aiken High, but they were mostly skirmishes at football games where students got into arguments with rival teams. The school had a good reputation in the community. Aiken High was also known for its wide range of extracurricular activities, including its robotics team and Taylor Swift Club.

Current and former students interviewed said they enjoyed their experience at Aiken High. They said the teachers were friendly, and they liked seeing their teachers and friends at football and volleyball games. When the teenagers weren’t in school, they liked to hang out downtown, going to restaurants on Friday nights or visiting the town’s golf courses where they played glow-in-the-dark golf or set up a manhunt. They felt happy and safe.

A former student said the school’s atmosphere changed at the end of last school year.

A social media challenge circulated, encouraging students to film fights in school for a week straight. A former student said her classmates were texting about it, but no one knew if anyone would participate. On Monday, she saw the videos.

They showed her classmates hitting and punching each other. At first, students thought it was funny. But violence escalated each day. By Wednesday, people were upset. No one focused on their work. Fights erupted in hallways, the cafeteria, and bathrooms. Teachers tried to break them up but weren’t trained for these situations. On Friday, the former student and many of her classmates refused to go to school because they were afraid. (Most current and former students the paper reached out to declined to comment for this story. One student told his parents, “Snitches get stitches.” Those who did agree to interviews did so on the condition of anonymity.)

The district said in 2021 that there was an increase in violence in the local community. There was also a rise in on-campus altercations. As part of the school’s effort to reduce fighting, a new assistant principal started in January 2022 to be in charge of promoting safety and security.

Parents said district and school officials told them the high school would be safer this school year. They said districtwide initiatives aimed at curtailing the violence should make a difference. That included a new year-round calendar that shortened summer break so students would have an easier time readjusting to classroom environments.

But small fights broke out during the first week of school, according to parents interviewed by the paper. After the Aug. 3 incident, Walker sat her daughter down for a serious talk.

“I told her, ‘You always have to be prepared for any and everything and to be cautious of weapons and stuff like that,’” Walker said. “I said, ‘You know what you need to do to keep yourself safe. If something happens, call me ASAP, and I’ll be there to pick you up.’”

Like other parents interviewed by the paper, Walker was upset that she had to have conversations like this with her child. She believed high school students should be focused on academics, not trying to avoid getting caught up in a brawl. Walker, and other parents, wanted the high school to change.

Social media and school violence

Calls for the students’ expulsions spread quickly over social media. People on Facebook said they should be sent to an alternative or home school. Several blamed the teenagers’ parents and said they should be raising their children better.

Parents interviewed by the paper said their children avoided bathrooms between classes because they were afraid of getting involved in a fight. They didn’t walk through the hallways alone. Some parents talked about a rumored social media page where students posted videos of fights for likes.

Tensions were high and boiled over during an Aug. 8 school board meeting. Matthew Bracket, a teacher at the school, stood up in front of the board and began to speak.

He said he was involved in two fights over the past several years. During one of the arguments, he had to restrain a young man who started attacking him. He said that community members are asking him if the school is safe, and he cannot answer that question the way he had in the past.

Aiken High School teacher Matthew Bracket addresses the Aiken County School Board during an Aug. 8 meeting regarding a fight that occurred at Aiken High School on Aug. 3, 2023. File/Erin Weeks/Staff

STAFF PHOTO BY ERIN WEEKS

He said he had seen students recommended for expulsion or who were expelled put back into the school. He said these students often fall back in with the crowd that influenced them to do the things that got them expelled in the first place. The violence resumed and distracted other students from their work.

“As I sit around and talk to educators and peers, we don’t sit around and talk about our lack of salary — we talk about the disappointment of seeing the same peers or repeat offenders who cause major disturbances in the school be put back into the hallways again and see history repeat itself,” he said.

The following day, a parent posted a video on Facebook of two young boys fighting in a classroom. The boys wore T-shirts and shorts and looked younger than 16. One boy shoved the other, and both began hitting ferociously. Two people tried to break up the fight, but other students looked on with bored expressions. When the two boys hit a table and almost fell on top of another student, the other student pushed them away. The person filming the video was laughing.

The video circulated among parents. Many thought it was filmed at the high school and taken the day it was posted. But the district told The Post and Courier in an email that it was filmed at a different school during a previous year.

The parent posted a second video on Aug. 14 of a fight in the school’s cafeteria. Two girls pushed against the people, dragging them away from each other. One broke free and started hitting the girl she was fighting over the head with her fist. A school resource officer who tried to intervene was shoved and fell to the floor. It took a group of people to finally pull the girls apart as their classmates yelled and cheered.

The district confirmed there was an altercation between two female students in the cafeteria and said the video “may be from that altercation” though it was unable to confirm it with certainty.

The parent who posted the videos didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment. As the videos were shared, criticism of the district reached fever pitch.

Mental health and school security

Aiken has a north and south side. Most of the city’s White residents live in South Aiken, while North Aiken is more diverse. Only a third of the roughly 22,000 students in the school district are Black, but Aiken High’s student population is split pretty evenly between the two races, according to South Carolina Department of Education data. All of the students the police charged with misdemeanors following the fight were Black, as were most of the students in videos showing the fight reviewed by the paper. In several Facebook posts about the Aug. 3 fight, people referred to the students as “thugs” and one person called Aiken High a “zoo.”

More coverage

To read more in-depth stories from The Post and Courier’s Education Lab, go to postandcourier.com/education-lab.

Mo Canady, executive director of the National Association of School Resource Officers, said increasing security measures is only one part of a three-pronged process that includes mental health counselors and educating students and staff about prevention tactics.

He encouraged school districts to invest in long-term solutions that would stop violence before it becomes a problem, like hiring more counselors. He said resource officers should see counselors as partners since they are all there to help students.

“The last thing we want to do is arrest a student and take them off campus; we hope that’s a rarity,” he said.

He pointed out that supporting students’ mental health is especially important post-pandemic. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found in 2021 that more than 42 percent of students felt persistently sad or hopeless, and over 22 percent seriously considered attempting suicide.

Vanya Jones, an assistant dean at Johns Hopkins’ Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, found that social media exacerbated the fighting. Historically, people learned how to negotiate conflict in person during their teenage years. They were able to identify frustration’s physical systems, like their ears getting hot or their chest getting tight. They learned how to calm themselves down while talking to someone in the moment. They also learned how to solve problems with words rather than fighting.

Social media changed this.

Now, students are insulted or called out by classmates in social media posts that all their classmates can see. These arguments escalate quickly over social media, with each party growing angrier and less in charge of their self-control. When they finally see each other in person in a school cafeteria or hallway, they don’t talk.

They fight.

Security upgrade

Aiken High made changes. The school also hired an additional resource officer, placed weapon-detection systems in school entryways for several days and conducted bag checks, according to a district statement.

The superintendent announced on Aug. 15 that he planned to retire at the end of the school year. The district said he “was not daunted by any public criticism and did not resign.”

Parents were pleased with the additional security measures. But they also knew there was a whole school year left to go.

Sign up for our Education Lab newsletter.